By Deborah J Smith, Wentworth Woodhouse Preservation Trust Research Group, 2023

Seventy-five years ago, the ‘Windrush Empire’ docked in East London, discharging its load of one thousand and twenty-seven official passengers and two stowaways-Caribbean British citizens, who answered the plea for help rebuilding what they regarded as their mother country. They may have met a sea of white faces on the docks that day, but they were welcomed into pre-existing black communities who had lived in Britain for generations. They took a well-trodden path from Empire to Britain.

Almost two hundred and fifty years ago, two young sixteen year olds made a very different journey – a winter crossing in the worst of weather from the American Colonies, aboard the British war sloop the ‘Tamar’.

They were called Romulus and Remus. They had no surnames. They were not entitled to them, for, of course, they were slaves. Nor did they choose to come here. They were being sent as a ‘present’- a thank you gift from the ex-Governor of New Hampshire, John Wentworth, to Lady Rockingham, for the care she had given his wife and son, the Rockinghams’ god-son, Charles-Mary.

In all probability, they had already faced one horrific sea voyage. They would have been captured as children of around 8 in the middle of the night by fellow countrymen raiding small villages, packed into slaving ships on the East coast of Africa and transported to New Hampshire, where those who survived the interminable voyage were sold on the docks.(1)

John Wentworth wrote on 1st of December 1776 from Long Island to the Marchioness of Rockingham expressing his effusive thanks and hoping she would honour him by accepting his ‘present’. (2) They were about sixteen years old (3), and had been with John Wentworth “since their childhood”. They were proficient at the French Horn, with Remus being described by his (music) masters (4) as having “remarkably good taste in music”; and both, Wentworth assured Lady Rockingham, were “faithful, honest and free from vice”.

Their arrival at the Rockinghams’ London house on Grosvenor Square sent the house into a flurry. We do not know what the Rockinghams’ thought of this ‘unsolicited’ gift, but they were not Lady Rockingham’s first black servants: from 1767, when the eleven or twelve-year old was christened, Henry Fryday, in Wentworth Church (5), until his burial at age 18 in the same church graveyard (6), Lady Rockingham had kept a black page to wait upon her. His origin is not known.

On their arrival, Lady Rockingham swung rapidly into action hurriedly redirecting liveries made for others and announced herself well-pleased with the result. Isaac Charlton, the butler wrote to Benjamin Hall the Steward at Wentworth Woodhouse “My Lady has a present made of two Blacks that plays the French Horn, they have had frock liveries made here. Her Ladyship likes the clothes so well that she has given orders for the frock liveries to be made immediately, for present wear.” (7)

In addition to any musical performances that they might be expected to play at (Lady Rockingham was very musical: at her husband’s death, she owned 4 harpsichords; and sang), their role was to announce her Ladyship’s departure from or arrival at the Grosvenor Square House, by blowing their French horns. They would also have attended her on her carriage, blowing their horns to clear obstructions on the road. (8)

The young men must have been fearful of their new mistress and what life in Britain would entail. But perhaps, they also had hopes of a better life and even freedom once they had left the shores of the war-torn colonies.

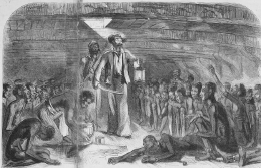

Georgian London was a heaving metropolis in comparison to anywhere in the Colonies: its population of 676,250 included around 15,000 black servants, most of them men (9). One in forty-five faces seen in the street were those of black servants, their numbers augmented by sailors, students sent to study in Britain, musicians in English military and domestic bands, and refugees from the Colonies who had fought on the Loyalist side in exchange for freedom.

The two young men must have found English society to be full of astonishing contrasts and extremes.

At the highest levels of Society, an “Ethiope Prince”, kidnapped and rescued from slavery, was feted by the aristocracy (10), and Prince William Henry was known to have kept a black Mistress; black footmen could duel, seconded by their white colleagues (11), attend Black Balls (12), send calling cards and host colleagues from other households at card parties (13); and the parks were full of fine ladies, their pale complexions exaggerated by poisonous lead-based makeup and the contrast with their black pages (14). It was also a place where black slaves were whipped and tortured, like Mary Prince whose mistress punished her cruelly for the slightest offence (15); where the newspapers carried regular notices of runaway slaves (16), who when returned as stolen property to their masters and mistresses, were sold on and tied to the masts of ships bound for plantations (17).

It was a place where a white thief could hang for cutting the purse of Joshua Reynolds’ black servant (18); and where the Lord Chief Justice of Britain, the Earl of Mansfield (and Rockingham’s Uncle (19)), left money to his beloved mixed-race grand-niece, Dido (20), insisting that she was born free, and trod a perilous line between the protection of individuals on English soil, and the protection of property-rights of slave owners against a slowly-swelling abolitionist tide of public opinion.

Romulus and Remus have not left us any account of their lives in the Rockingham’s household. However, the records show that by 4th May 1782, they are listed as Footmen in the London House in the Steward’s Memoranda Book in the List of Servants liable to be taxed; and they have acquired surnames: Romulus chose Wimbledon – named perhaps for the beautiful house in the country that the Rockingham’s retreated to whenever their London lives allowed them to – and Remus chose Stan(d)field probably after James Field Stanfield (21), the first sailor involved in the horrific slave trade to turn abolitionist and pamphleteer.

The pair accompanied the Marchioness to Wimbledon and then Hillingdon, after the sudden death of her husband in 1782. By this time, British law gave them some degree of protection, allowing them to leave their masters if they chose – although this was largely an empty freedom to starve and slavery would not be abolished until 1833.

Romulus was ill in 1790, and wrote his will leaving his musical instruments, all his music and reading books, and his clothing to his friend, Remus; and left monetary gifts from his stocks and shares to his friends among the servants including to Martha Woodhead for nursing him and Bettey Kirkland, the Cook, for her care of him during his illness. He was clearly being paid – and had earned enough to save towards an annuity that would provide for him when he could no longer work. He rallied and did not die until October 1792. Perhaps it is telling that his closest other relationship was with a coal merchant, who was named as his executor; perhaps he felt the cold!!!

Remus married Martha Booth in 1790/1 and had 9 children over the next 18 years – the first of three of these were born at Hillingdon. When the Marchioness died in 1806, she left “Remus Standfield late of her service” an annuity of £25 for his lifetime – worth around £2,870 per year.

He died in November 1828, aged around 78, in Cobham, Surrey. His direct descendants still survive.

1 Leech, Adam, Slave Trade: Centuries Later Portsmouth Remembers the Forgotten, publ. 2007.

Retrieved 19 Nov 2023.

2 DD/RA/F/2a/52/1-c December 1st 1776, Letter from Governor Wentworth to Lady Rockingham, (c) WY Kirklees Archives. Published with permission, from the collection of Isabella Ramsden, daughter of Thomas 1st Lord Dundas.

3 Romulus’ burial is registered in 1792 and gives his age as 42. Westminster, London, England, Church of

England Bapsms, Marriages and Burials, 1558-1812 City of Westminster Archives Centre; London, England; Westminster Church of England Parish Registers; Reference: STJ/PR/8/4 publ by Ancestry.com

4 This has been misinterpreted by other scholars who have assumed that the young men had been previously owned by other masters but a careful reading of the text suggests otherwise. Adam Leech writes that slaves of high status households were educated to enhance their masters’ status Slave Trade: Centuries Later Portsmouth Remembers the Forgotten, publ. 2007. Retrieved 19 Nov 2023.

5 Baptised in Wentworth, 6 May 1768 “England, Yorkshire, Parish Registers, 1538-2016”, Doncaster Archives, database, FamilySearch.

6 He was buried 18 August 1773 Yorkshire Burials, Doncaster Borough Council – Henry Friday.

7 WWM Stw p 6 (I) – 145 published with permission from Sheffield Archives. The Wentworth Woodhouse Muniments have been accepted in lieu of Inheritance Tax by HM Government and allocated to Sheffield City Council.

8 http://drmarcsblog.marcrochester.com/2017/10/black-scottish-horn-players.html

9 In 1768, Granville Sharp and others had put the population of black population of London at around

20,000,but Gretchen Gerzina, Black England: A Forgotten Georgian History published by John Murray, rev.

2022 estimates closer to 15,000.

10 Wednesday 9 May 1759 two Africans, one a recently rescued enslaved prince, were given a standing ovation at a production of Ooranoko at the Theatre Royal Drury Lane. Wylie Sypher ‘The African Prince in London’, Journal of the History of Ideas, Vol II, No 2 (April 1941).

11 The incident happened behind Montague House, in 1780. Hecht, Continental and Colonial Servants, p47.

12 London Packet, 26-29 June 1772,no. 418,le. Almost 200 attended a Black only Ball in celebration of the

decision of William Murray, Lord Chief Justice Mansfield, that it was unlawful for Charles Stewart, a Boston customs official, to forcibly transport James Somerset, an enslaved African bought in Virginia, out of England.

13 London Chronicle, 1757, II, 263c. Cited by Hecht The Domestic Servant Class in Eighteenth-Century England published by Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1956, 214-15

14 ‘The Black Man’ in All Year Round, 6 March 1875, 491

15 The Classic Slave Narratives, Henry Louis Gates Jnr (published by New York: New American Library, 1987,189, 54 The History of Mary Prince.

16 Eg. 1768 ’Ran away from his master, a Negro boy, under 5 feet high, about 16 years old, named Charles, he is very ill made, being remarkably bow legged, hollow backed and pot-bellied; he had when he went away a coarse dark brown Linen frock, a Thickset waistcoat, very dirty leather breeches, and in his head an Old Velvet jockey cap’ cited by Walvin, The Black Presence, 79-80.

17 The cases of James Somerset, 1772, and Grace Allen, 1822.

18 Northcote, James, The Life of Sir Joshua Reynolds, published Henry Colburn, 1819, Vol1, 204-6

19 William Murray, 1st Earl of Mansfield married Elizabeth Finch, younger sister of Rockingham’s mother, Lady Mary (Finch), 1st Marchioness of Rockingham.

20 Dido Elizabeth Belle (1761-1804) was the illegitimate mixed-race daughter of Sir John Lindsay, RN and Maria Bell, a previously enslaved woman, who bought her own freedom 22 August 1777. Dido became the ward of her great-uncle, alongside her white cousin Elizabeth, and was a much loved, respected and valued part of her uncle and aunt’s household at Kenwood. When he died, he let her an annuity of £100 and a lump sum of £500 (approx £40,000 in today’s money).

21 Lee, Sidney, ed. (1898). “Stanfield, James Field” . Diconary of Naonal Biography. Vol. 53. London: Smith, Elder & Co.