Over the centuries many people have had a fascination for exotic animals and birds from around the globe. King Henry I (c.1068-1135) kept a collection of ‘wild beasts’ including lions, leopards, camels, hyenas, lynxes and even a porcupine – many, gifts from other European monarchs. There was a menagerie in the Tower of London as early as 1204. In 1235 the Holy Roman Emperor sent Henry III three leopards; the King of Norway sent a ‘white’ bear (which apparently was allowed to swim in the Thames) and in 1255 Louis IX of France sent Henry an African elephant!¹

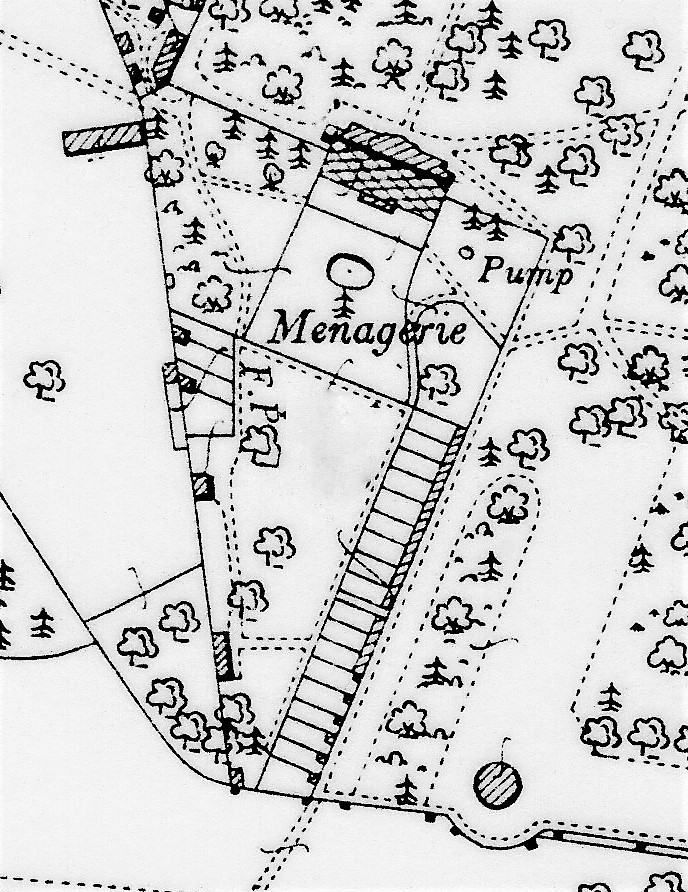

As trade and travel increased, seamen and merchants began to offer animals and birds to those who wished to develop their own menageries and aviaries. Royalty and aristocrats created them for their own interest and amusement and to demonstrate their wealth, status and foreign connections. Successive owners of Wentworth Woodhouse were no exception. In 1737 Thomas Watson-Wentworth (who became the 1st Marquis of Rockingham) noted in his journal that ‘the new Menagery [was] taken in’. In the following year he wrote ‘the pavilion [a tea-house] and Green House [later called the Camellia House] at the upper end of the menagerie were all then Built’.² This reference located the menagerie around the Camellia House. The area was still labelled ‘menagerie’ on maps in the 20th century so existed for almost 200 years in some shape or form.

The rectangular building marks the Camellia House and the circular building marks the Ionic Temple.

Initially it may have been an aviary according to descriptions by two travel writers who visited Wentworth Woodhouse. In 1750 Dr Richard Pococke was impressed by ‘the menagerie in front of the green house containing a prodigious number of foreign birds, particularly gold and pencil pheasants, cockatoos, Mollacca doves etc’³ and in 1768 Arthur Young said that ‘the aviary was housed in a ‘light Chinese building of a very pleasing design stocked with Canary and other foreign birds’ which were ‘kept alive in winter by means of hot walls at the back of the building; the front being an open net-work in compartments’.⁴

In the late 18th century a few records exist and throughout the 19th century there are more detailed accounts of animals and birds in the menagerie and of their careful management.5 The 2nd Marquis of Rockingham had a female moose as early as 1770. This was one of the earliest moose to be imported into England from North America. Evidence of this female comes from a letter to the Marquis from the Duke of Richmond who was anxious to breed his male moose (which George Stubbs painted) with the Marquis’s female moose. This female was kept ‘at Rockingham’s seat at Wentworth in Yorkshire’. It was said to be ‘a mild animal’ but was ‘uneasy and restless in the presence of others’ and ‘made a plaintive noise.’6 Sadly we know no more! In June 1788 William Stear was paid for the freight and keep of another moose ‘from Goul Bridge to Cinder Bridge’. It had obviously been brought from the east coast via Goole on the Humber, on the navigable River Don and then along the Greasbrough Canal to its terminus at Cinder Bridge just to the east of Wentworth Park. In November of the same year Daniel Whealand was paid £7-10s-0d for bringing another moose from America. 7

The variety of animals and birds in the menagerie in the 19th century is astonishing. Altogether records have been found of eighty-nine species; sixty-two species of birds and twenty-seven species of mammals (excluding the buffaloes in the park) – and there may have been more.

The birds included four species of eagle, four species of owl, three species of pheasants, macaws, parrots, lovebirds, two species of seabirds (cormorant and guillemot), emus, black swans and trumpeter swans.

Among interesting yet uncommon European species were shrike, golden oriole and a kingfisher (with its nest!). Mammals included alpacas, agoutis (a small forest browser) a tapir and a tiger cat from South America; an African goat, mongoose rat and three species of lemur including the ring-tailed lemur from Africa.

Other mammals included, an Indian antelope, an axis deer, a Java hare and a Cashmere goat from Asia; a wombat, female kangaroo with a ‘joey’ in its pouch from Australia, a raccoon and a brown bear from North America. Was the bear kept in the bear pit, located next to the Japanese garden?

There are three remarkable records that tell us about the ardent desire to collect and breed rare animals and the family’s attitude to the animals and birds in their care. The first is an entry in the account books for 1841 which records the payment of £31-9-1 for four llamas from Arica in northern Chile and their transport to Liverpool at a cost of £20-15-0. The second is that later that same year, on 9th September, the Doncaster Gazette reported the ‘birth of an extraordinary nature … at the menagerie at Wentworth Woodhouse. The Noble Earl Fitzwilliam is in possession of a male and female llama … very rare in this country … The female has produced one young one perfectly white in colour and healthy in appearance…’.

The third is a report in the Sheffield Daily Telegraph in 1873 about a visit to the menagerie organized for the 6th Earl’s coal miners. Apparently they were guided around by a ‘genial old lady’, presumably one of the Earl’s menagerie keepers, who pointed out ‘the ostrich, the emu, the armadillo, the orang-outang, and the chimpanzee’ who ‘was fed on port wine and biscuits and attended to just as if he had been a Christian’. That thought that the menagerie keepers at Wentworth Woodhouse were held in high regard is reflected in the fact that James Thompson was recorded as the menagerie keeper in the 1851 census when he was living at Friar House in Wentworth, but by 1861 he was Keeper of Animals in the Zoological Gardens at Regent’s Park in London.

Vets made regular visits and the keepers provided the best living conditions that they could. Accounts show food being purchased – ‘sheep’s Heads and Hearts for the Eagle’, rabbits, mice, seeds, corn and grain. Inevitably some animals died of illness and old age and a museum was created for displaying stuffed animals and birds and mounted skeletons. Between the 1830s and 1850s Hugh Reid was paid an annual fee for ‘preserving and stuffing birds and providing them with cages’. Reid was a taxidermist of some renown who lived in French Gate in Doncaster. In 1841 ‘H. Chapman was paid £4-5-0 for mounting the skeleton of an Antelope’ and in 1843 Charles Cooper was paid £12-13-0 for ‘preparing the skeletons of a llama’…let’s hope it wasn’t the baby llama born in 1841.

To us in the 21st century it may seem horrific to keep animals and birds in captivity with less sophisticated knowledge than we now have about their care, but for 18th and 19th century visitors to Wentworth Woodhouse (aristocratic friends, travel writers and invited members of the local population) it must have been amazing to see these creatures from across the globe before the days of photography and film.

References

- Caroline Grigson, Menagerie: the History of Exotic Animals in England 1100-1837, Oxford University Press, 2016

- Wentworth Woodhouse Muniments WWM/A/1273, Sheffield City Archives (SCA)

- Dr Richard Pococke, Travels through England during 1750-51, Vol.1, edited by James Joel Cartwright, 1888, Camden Society, Westminster

- Arthur Young, A Six Months’ Tour through the North of England, 1768, W. Strachan, London, 1771

- WWM/A/38 Household Accounts, SCA

- WWM/R/1/1316 with permission from The Milton (Peterborough) Estates Co & SCA

- WWM/A1-A220 Household Accounts, SCA

Joan Jones

Volunteer Researcher