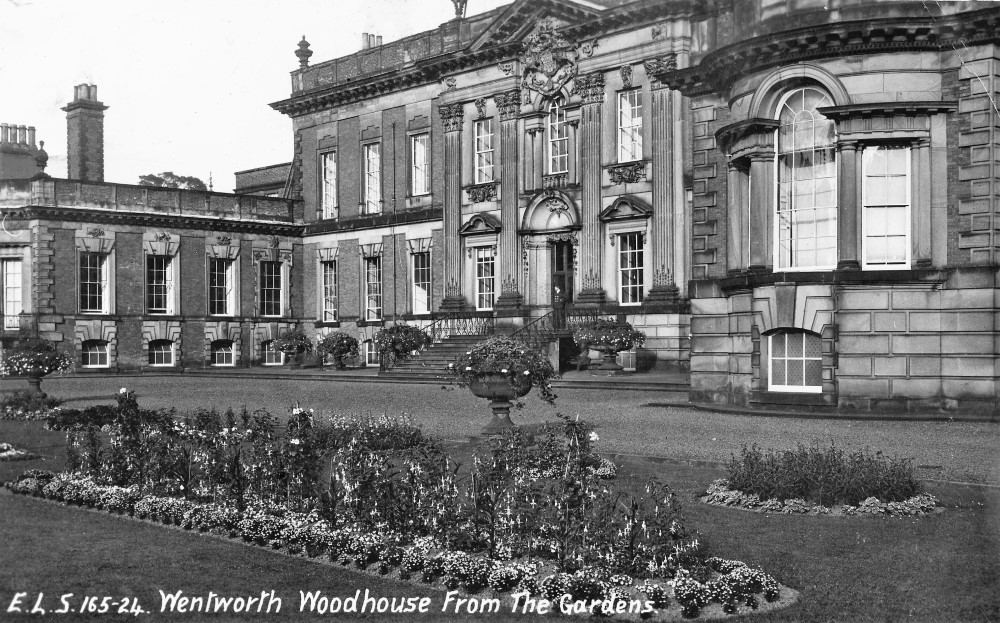

‘…large and noble, with delicate walks and groves’ Ralph Thoresby, 1711

It seems that there has been a love of gardening at Wentworth Woodhouse since at least the 16th century. The early evidence is from a painting by John Lavorgne which shows Thomas Wentworth (who died in 1587) sitting and holding, in his right hand, a tree stock in which grafts have been inserted and in his left hand he holds a grafting saw with a serrated edge and a knife. Also shown are his wife, Margaret; daughter, Elizabeth; and his head gardener in the family livery. Behind the figures, very faintly, knot gardens and the early mansion are just visible.

Formal Splendour – 18th Century Developments

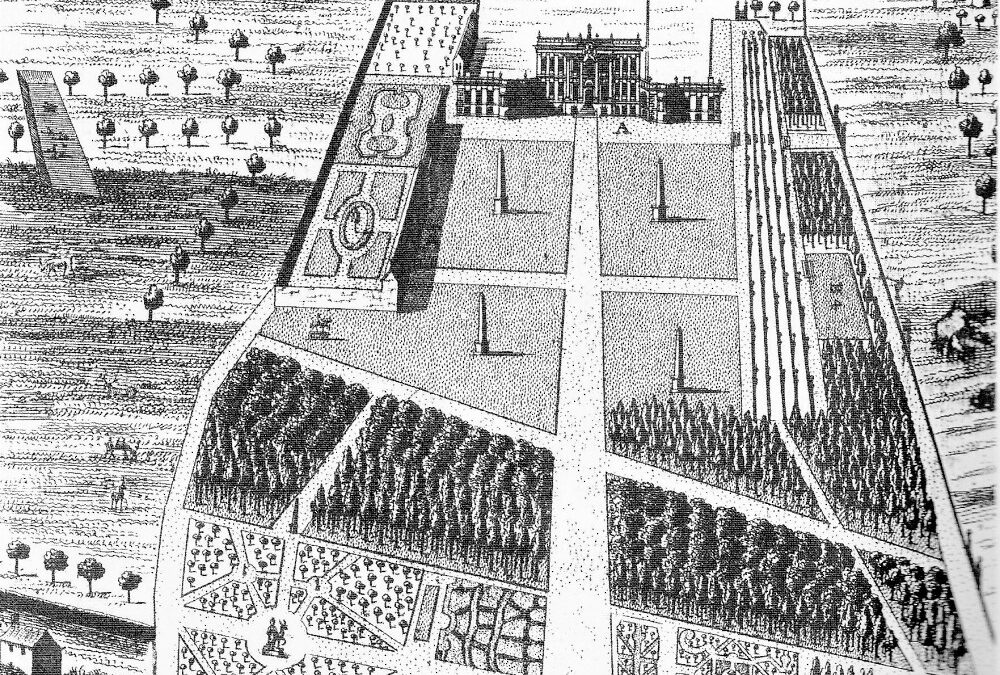

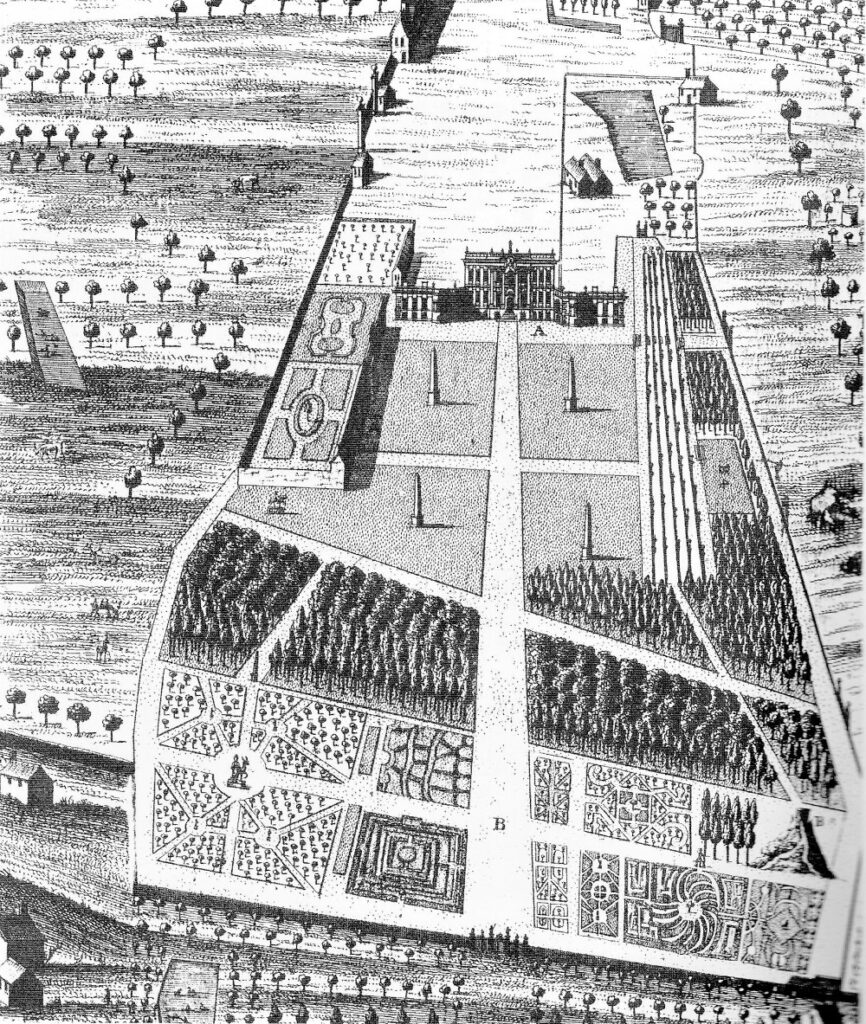

A wonderful engraving of c. 1730 by John Cole is held in the Bodleian Libraries.1

It shows the gardens running westwards from the Baroque side of the mansion. The elaborate garden had a large lawn divided into four by straight paths. In the centre of each section stood a large obelisk placed there in 1729, although the future 1st Marquis of Rockingham may have regretted their positioning when Horace Walpole said that the view looked like a bowling green! These four stone obelisks were moved in 1793 to adorn the Rockingham Monument at the suggestion of Humphry Repton, the famous landscape garden designer.

To the south of the lawns were what appear to be espalier fruit trees on terraces and an enclosed bowling green. On the northern side of the lawns were an old range of buildings and parterres. Further west were plantations of trees, parterres, knot gardens and a maze. Excitingly there was even a ‘mount’ – a constructed hill – said to be 100 feet high where family members and guests could climb a winding path to the summer house on the summit to admire the garden.

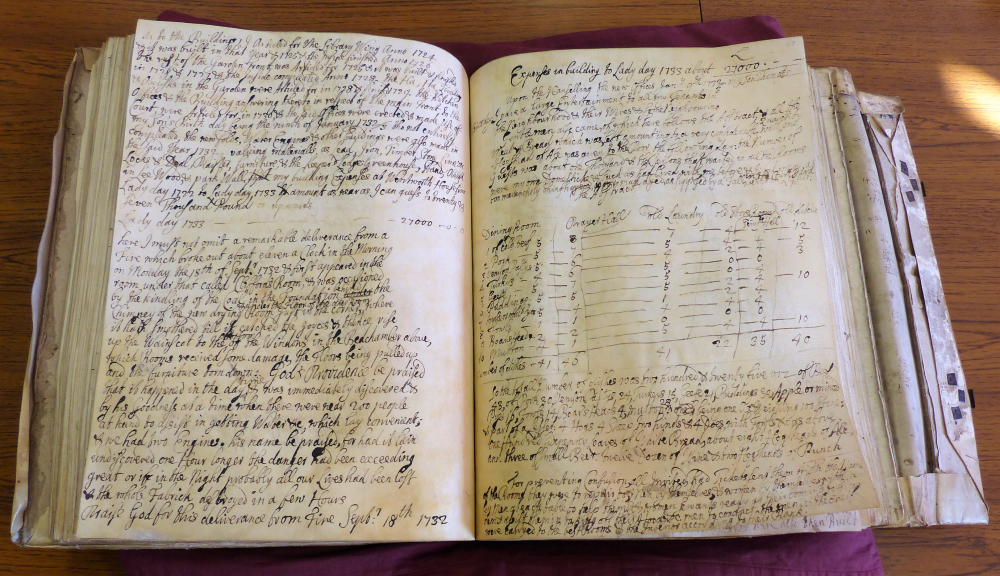

Further 18th century evidence comes from a large volume deposited in Sheffield Archives2 written by Thomas Watson-Wentworth who became the 1st Marquis. It is 16”x 12” with almost 90 pages of handwritten notes on vellum fastened with 2 metal clasps.

One section is devoted to rents but another is entitled ‘many remarks and observations’ in other words it was his journal. He included details about the park and the gardens. In 1735 and 1736 he wrote that the terrace, ice-house and temple were constructed.

The Terrace

Work on the 1,500 ft (c. 457m) terrace was started in 1735. It has a tremendous retaining wall with a bastion at its eastern end and the Ionic Temple at the western end. Terraces were popular for outdoor exercise and for showing off your estate! Ralph Tunnicliffe supervised the building of the terrace wall. In the spring of 1736 part of the wall collapsed, possibly due to inadequate foundations. Tunnicliffe was held responsible and this set-back caused a delay in work on the east front of the mansion because workmen were taken away to repair the damage. Tunnicliffe died in 1736 and Henry Flitcroft then took charge of all the building projects.

When Dr Richard Pococke, a travel writer, visited in 1750 he noted that kine (cattle) were kept in the meadow beneath the terrace. In 1768 Arthur Young, another visitor, described the view from the terrace saying ‘…the eye is continually feasted with an exceeding fine and various prospect of hills, dales, winding water, hanging woods, temples, and noble sweeps of park.’ 3

The Ice-House

The ice-house, near the stable block, was built to supply ice to the kitchens before the days of insulated boxes or refrigerators. The ice was used for storing meat and fish in the summer months and for making desserts and for cooling wines. The ice was collected in winter from the frozen lakes and ponds in the park and gardens and taken by cart to the ice-house. Inside would be a sunken chamber to store the crushed ice. The Wentworth Woodhouse accounts show that the ice-house was once thatched to provide insulation. Among the records in 1797 Adam Holding was paid £1-10s-0d for thatching and in 1810 Jonathan Baildon received £3-7s-1d. What is interesting is that even in the early 1950s only 2% of British households had a fridge.

The Ionic Temple

At the western end of the terrace is the domed temple. It has ten Ionic columns – slender elegant pillars with scroll-shapes at the top.

The columns encircle a statue of Hercules fighting a mythical beast. Hercules is dressed in the skin of a Nemean Lion and wields a club as he battles the monster. According to Greek mythology the Nemean Lion had golden fur which was impervious to attack by weapons or, one assumes, the mythical beast!

The Greenhouse and Pavilion

The 1st Marquis mentioned the Green House in 1738, the building that we now call the Camellia House, stating ‘…. the Pavilion and Green House at the upper end of the menagerie were also then built’. These are shown on a watercolour plan of c. 1760 4 and in 1768 the travel writer, Arthur Young, mentions the greenhouse saying it is ‘very spacious, and behind it a neat agreeable room for drinking tea.’ 5 ‘Taking tea’ was a popular 18th century pastime among the gentry and ‘middling’ classes.

On the watercolour plan are two ‘skittle greens’. In 1750 Dr Richard Pococke commented that the skittle grounds were ‘for the young to divert themselves.’6 By the 1770s much of the formal layout to the west of the mansion had disappeared – apart from a small area on the SW labelled ‘The Marchioness’s Flower Garden’. The knot gardens and parterres had been replaced largely by shrubs and trees.

The Kitchen Gardens

Prior to the 1780s the kitchen gardens were situated to the east of the mansion. Now the view from the vast Palladian front of Wentworth Woodhouse is of rolling parkland, modified by Humphry Repton, in the early 1790s at the request of the 4th Earl Fitzwilliam.

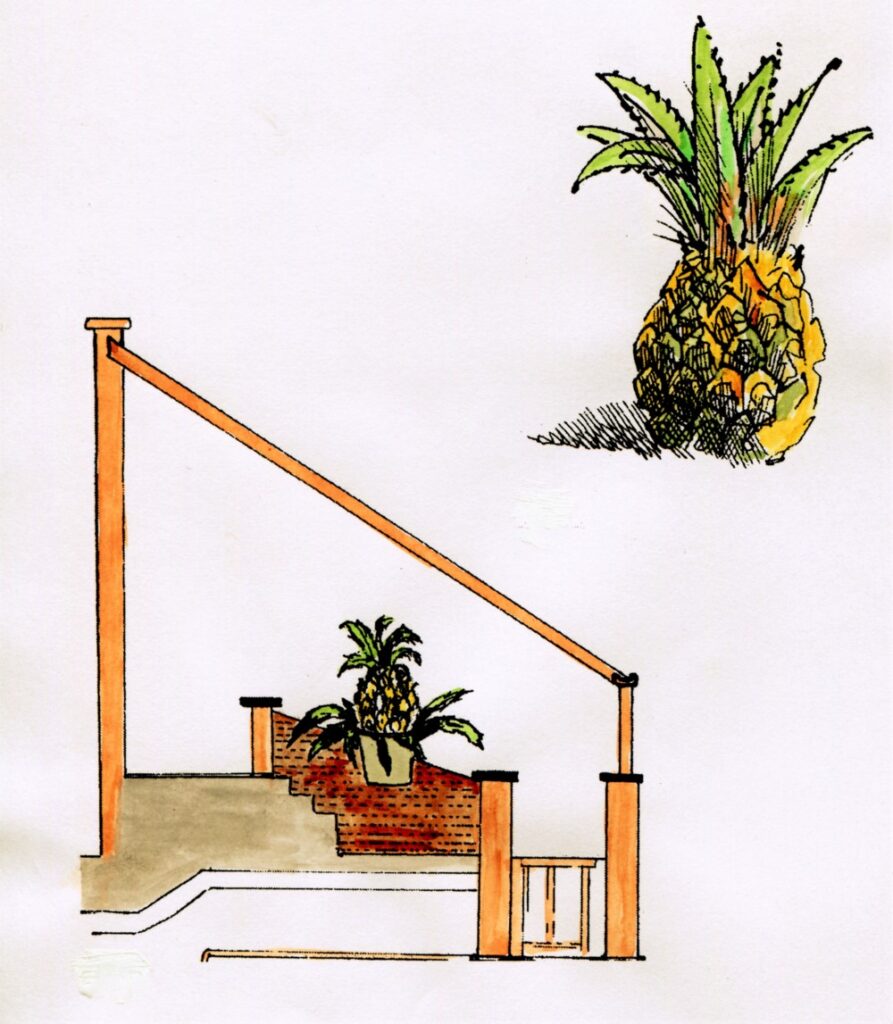

The kitchen gardens produced an amazing variety of fruit, vegetables and flowers. The quality and range of fruit and vegetables on the dinner table were status symbols and a measure of wealth. The 1st Marquis mentioned the growing of pineapples in 1737 when he noted that they were then ‘very scarce in England’. At this time it was said that large landowners were in the grip of ‘Pineapple Fever’. By 1740 he said that he had got their cultivation ‘to great perfection’ and boasted that one weighed 3½ pounds! In 1745 he said that he had cut 200 that year and had some sent to his London residence for ‘an entertainment I made’.7 The fruits were often placed as a centre-piece on the dining table not necessarily to be eaten but to be admired – and envied! Some were even hired out as decoration for dinner parties.

Pineapples were first grown in so-called ‘tan pits’, an innovative idea first trialled in Holland. These were brick-lined pits with a back wall to which sloping glass frames were fixed.

The pits were then filled with rubble on which used tan bark (waste oak bark from the leather tanning process) was laid. The discarded bark ferments producing heat. The pineapple pots were sunk into the tan bark which kept the temperature between 75-85° Fahrenheit. This was adequate heat from March to October. The pineapples were then moved into heated conservatories for the next six months. Pineapple suckers and crowns were passed around friends. In 1753 the 2nd Marquis was receiving ‘Pine Plants’ from the Duke of Devonshire and Sir Rowland Winn. He was sending others to the Bishop of Asaph and the ‘Duke of north norfolk’.8

In 1746 the 1st Marquis wrote that he had ‘presented His Majesty [King George II] with a Bunch of Frontiniak Grapes & one of Muscadine perfectly ripe, which he did eat the day after he received the news of the Dukes Victory over The Rebels in Scotland.’9 This was the putting down of the ’45 Rebellion.

Other fruits being grown under glass or with protection were water-melons, peaches, apricots, nectarines and even bananas. In 1780 the 2nd Marquis compiled a list of ‘Exotic Plants at Wentworth’. There were about 350 different varieties of flowers not to mention the array of vegetables and other fruits. In 1794 the gardens were cared for by 27 gardeners (including four women).

National Fame – 19th Century

There was an incredible flurry of garden expansion in the early 19th century with a new kitchen garden (now the heart of Wentworth Garden Centre) and new glasshouses. The building we now call the Camellia House was modified in 1812 to a design by Charles Watson keeping masons, glaziers, plumbers, carpenters and painters busy for years.

From the 1830s a botanic gardener called Joseph Cooper was employed and became nationally recognised for his work. He was highly regarded in horticultural circles and said to be one of the ‘most zealous and successful cultivators of rare plants in this kingdom’. One of his specialities was the growing of orchids and he named one Orchid Miltonia after the 5th Earl Fitzwilliam. Viscount Milton was the courtesy title of the eldest Fitzwilliam son and the Fitzwilliam family home was Milton near Peterborough – hence Orchid Miltonia. The orchid is a gorgeous deep pinky-red with white markings and is still available to purchase. You can even buy tiles and tea-shirts with the Orchid Miltonia printed on them! A white six-petalled amaryllis was named after Joseph – Geus Cooperia – praise indeed! An interesting garden feature of this period is the ‘Punch Bowl’ near the eastern end of the terrace. It is a 15-ft high stone urn carved with the date 1837, designed to be lit on special occasions.

In 1866 the Gardeners’ Chronicle noted that Joseph Henderson (head gardener at Wentworth) had a special interest in ferns and that the collections at Milton and Wentworth were among the most important in the country. In the mid-19th century 50 gardeners were employed and the kitchen garden flourished, as did the ornamental gardens to the west of the mansion. A report in 1888 in the Illustrated London News10said that the view of the gardens was that of ‘a lovely greensward bordered with rare trees of the softest, deep colour with cut hedges and winding beds, one bed of violas of a glowing purple-blue – quite unforgettable’.

The landscape to the east, at this period, was grazed by deer, cattle and even bison. In 1881 two bison escaped causing much commotion in the locality!

Parties and Plunder – 20th Century

Until the Second World War the gardens were still much loved by the family and enjoyed by many visitors. Countess Maud (the 7th Earl’s wife) was a keen gardener and a stalwart fundraiser for charities.

She regularly opened the gardens for events, with bands, comic entertainment, displays, competitions and plant sales. Locals flocked in their thousands and Countess Maud could sometimes be seen in an apron at a plant or flower stall.

It was these gardens that were cruelly destroyed in pursuit of opencast coal after World War 2. While the 8th Earl pleaded with Prime Minister Attlee for the gardens to be spared an excavator was moving 130 tons of earth an hour, working through the night under lamplight. Roger Dataller, a local writer and broadcaster, wrote a scathing article in the Northern Review in September 1946 about ‘a piece of vandalism’ where he had witnessed ‘great tracks scored in the ground with daffodil bulbs uprooted by the thousand, and white and wounded trees tumbled in the grasses’. It was a scene of desolation.

A combination of other factors contributed to the progressive decline and change after the 1950s. The area in and around the kitchen garden was operated for a period as a market garden. From the 1970s it began to develop as a garden centre. In 1999 Clifford Newbold purchased the mansion and the west-facing garden and began improvements there. Scott Jamieson was appointed head gardener and many rare species of shrubs were planted and a double herbaceous border was created.

And Now…

Scott is head gardener for the WWPT and the restoration programme continues. Scott, with two teams of volunteers, works tirelessly to maintain the 83 acres of gardens owned by the Trust and thousands of spring bulbs have been planted, an orchard established and a meadow created.

The Camellia House is being restored and the 19 spectacular camellias, some over 200 years old, will be cherished again.

So please do visit and often, in every season.

Joan Jones

Volunteer

References

- The Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford, Gough Maps 35, Folio 48

- Wentworth Woodhouse Muniments (WWM) A/1273, Sheffield City Archives (SCA)

- Arthur Young, A Six Months’ Tour through the North of England, 1768, W. Strachan, London, 1771

- WWM/MP/6/d (SCA)

- Arthur Young (op. cit.)

- Dr Richard Pococke, Travels through England during 1750-51, Volume 1, edited by James Joel Cartwright, 1888, Camden Society, Westminster

- WWM/A/1273 (op. cit.)

- WWM/R73-26 with permission from The Milton (Peterborough) Estates Co & Sheffield City Council

- WWM/1273 (op. cit.)

- The Illustrated London News, 8 September 1888 p. 284